Wealth Guide Number One

Most us would like to beat the market, but as we’ll explore in this whitepaper, even many professional money managers have had a hard time performing better than the market. To understand Active investors (and active money managers) attempt to outperform stock market rates of return by actively trading individual stocks and/or engaging in market timing — deciding when to be in and out of the market.

Given declines in global stock markets, many investors have seen little to no real growth in their portfolios over this period. For example, $10,000 invested in the S&P 500 Market Index in 2000, was worth just $10,681 at the end of 2011. And this does not take into account inflation, investment fees and taxes.1

Threat 1: The Expenses of an Active Market

Asset class mutual funds are called passive or “market” investors. Active mutual fund managers are typically compared to a benchmark index. For example, large cap mutual funds are often compared to the S&P 500 index. To beat the index, an active mutual fund must perform better than the weighted average return of those companies in the index. And they must do so while including fees, taxes, trading costs, etc. so they report a real rate of return.

A lot of time and money is spent attempting to “beat” the market. Professor Ken French of Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business estimates that investors collectively spent $102 billion per year in trying to achieve above-market rates of return.2 Professor French added up the fees and expenses of U.S. equity

mutual funds, investment management costs paid by institutions, fees paid to hedge funds, and the transaction costs paid by all traders, and then he deducted what U.S. equity investors would have paid if, instead, they had simply bought and held a passive pay trying to beat the market.

Threat 2: Many Active Mutual Fund Managers Have Failed to Beat the Market

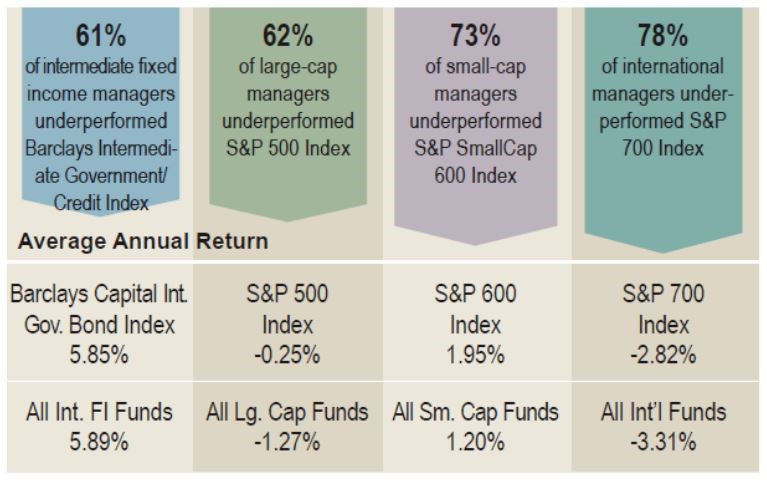

As you can see from this chart, over the five-year cycle from 2007 to 2011, the vast majority of active mutual funds underperformed the stock and bond markets.

Though past performance is no guarantee of future results, notice how many of the money managers’ average annual returns were below the average returns of their benchmarks. For example the average return for all Large Cap funds during this period was more than 1% below the Large Cap S&P 500 Index.

Mutual Fund Manager Performance from 2007 – 2011

Source: Standard and Poor’s Index Versus Active Group, March 2012.

While some managers were able to beat the market, this raises the question: was it luck or skill?

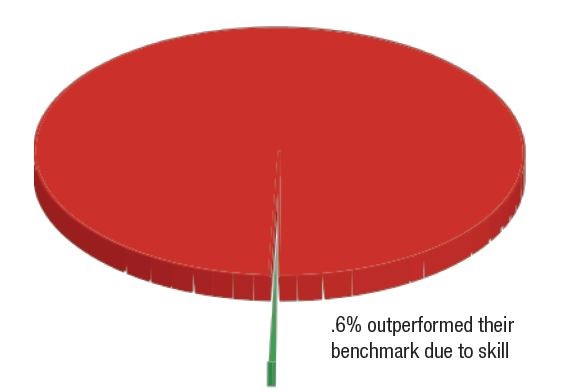

Universe of Active Mutual Fund Managers 1975-2006

In a 2008 research study3 — perhaps the most comprehensive ever performed — Professors Barras, Scaillet, and Wermers used advanced statistical analysis, to evaluate the performance of active mutual funds. They looked at fund performance over a 32-year period, from 1975-2006.

The study concluded that after expenses, only 0.6% (1 in 160) of active mutual funds actually outperformed the market through the money manager’s skill.

This low number “can’t eliminate the possibility that the few [funds] that did were merely false positives,” just lucky, in other words, according to Professor Wermers.4

Threat 3: Few Active Mutual Funds Have Outperformed in Bear Markets

Some have claimed that active managers have a distinct advantage in bear markets. They can get out of troubled stocks and sectors early and avoid the worst of a downturn.

Standard and Poor’s has been measuring the performance of active managers against their index counterparts for several years now.

Indices Versus Active Funds Study specifically focuses on the bear market of 2008 and concludes that “the belief that bear markets favor active management is a myth.”5

In the same study, Standard and Poor’s identified similar results for the 2000 to 2002 bear market. In both that bear market and the one in 2008, a majority of active funds underperformed their respective S&P Index for all U.S. and international equity asset classes. In aggregate in 2008, actively managed funds under- performed the S&P 500 Index by an average of 1.67%.6

One of the greatest challenges for active managers is the extreme difficulty in forecasting the economy or accurately predicting the market’s direction in advance. This makes it hard for them to anticipate bear and bull markets.

In fact, Wall Street has a notoriously bad forecasting record: its consensus forecast has failed to predict a single recession in the last 30 years.7

Looking back on the forecasts made for the markets at the beginning of 2008, just before the greatest bear market since the Great Depression, many of them turned out to be quite optimistic.

At the end of 2007, Newsday gathered market predictions from “eight major Wall Street Securities firms” and found an average price target for the S&P 500 by year-end 2008 of 1,653, representing a 12% increase over 2007. And at the beginning of 2008, USA Today similarly surveyed nine Wall Street investment strategists. They were a little less optimistic, expecting an average price target for the S&P 500 for the year of 1606, only an 8.6% increase. Of course, we now know that the S&P 500 Index declined by 37% in 2008. And many of those major Wall Street firms experienced their own unforeseen troubles, including being sold or merged.

If Wall Street experts can’t even predict recessions or the direction of the market, it is questionable how active managers can successfully pick individual stocks, in bear markets or bull markets, especially since a stock’s performance is often very sensitive to economic and market conditions.

Threat 4: Only a Few Stocks Have Generated

Strong Long-Term Returns Over The Last 20 Years

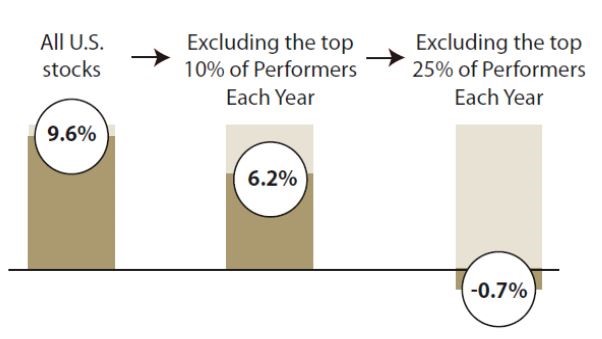

The performance of individual stocks differs greatly even though stocks collectively have historically provided strong returns over long investment horizons.

Looking at the University of Chicago’s CRSP total market equity database as representative of the U.S. market for the period 1926-2011, only the top-performing 25% of stocks were responsible for the market gains during this timeframe. The remaining 75% of the stocks in the total market database collectively generated a loss of -0.7%. This example demonstrates the difficulty in selecting the individual stocks that will perform better or even in-line with the broad equity market. It is important to note that past performance in any security is not indicative of future results.

Results based on the CRSP 1-10 Index. CRSP data provided by the Center for Research in Security Prices, University of Chicago.

One might ask: if a small percentage of stocks could possibly account for the market’s long-term returns, why not avoid all the headaches and just invest in these top-performing stocks?

Since past performance is not indicative of future results, a portfolio of even the most carefully chosen stocks could easily wind up with none of the best-performing stocks in the market— and thus could possibly produce flat or negative returns for many years. As the performance of active managers versus indices shows, very few managers are accomplished stock pickers.

Missing out on even a handful of the top-performing stocks can leave you well short of market returns. According to an article by William J. Bernstein in Money Magazine (05/09), the only way you can be assured of owning all of tomorrow’s top-performing stock is to own the entire market.

Threat 5: Missing the Best Days in the Market Can Lower Returns

Many active investors try to move much or all of their money out of the market when they believe a bear market or down cycle is imminent. However, this may result in missing not just down days but some of the best (most bullish) days in the markets as well.

This mistake can be dangerous to your wealth!

Missing even a few of the best days of the market can have a substantial impact on a portfolio. If you had invested $100,000 in 1970, it would be worth $5,066,200 in 2011. Missing just five of the best days would have cut your returns by almost $1.8 million to $3,294,000.8

No one knows when those “best days” will happen, yet some people prefer to try and ride out a bear market by pulling out of the market or just staying uninvested on the sidelines.

Even if you’d missed just one day — the single best day — between 1970 and 2011, you would have made a $500,000 mistake.

Threat 6: Lack of Patience and Discipline Can Be Costly

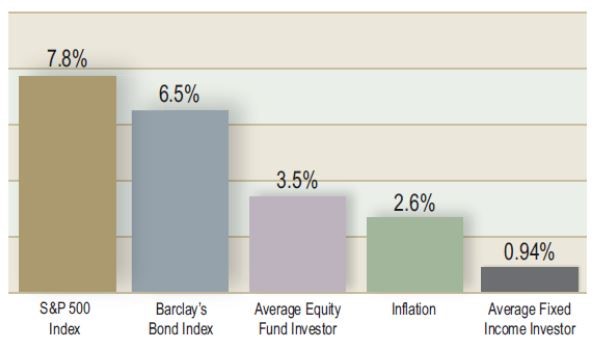

As the chart below shows, a study by the research organization Dalbar found that from 1992 – 2011, the average investor did substantially worse than major indices. Sometimes, we really can be our own worst enemies. Up and down markets can be emotional events, but as the study found, letting emotion affect your investing can be very damaging.

In this study, the average investor returns were calculated as the change in assets after excluding sales, redemptions and exchanges during the period. This method of calculation captures realized and unrealized capital gains, dividends, interest, trading costs, sales charges, fees, expenses, and any other costs.

According to this study, the average equity investor had annual returns of just 3.5% during this time frame. Over the same period, the S&P 500 returned an annual average of 7.8%. This almost 55% decrease in average annual returns experienced by the average investor is the cost of not exercising patience and discipline, of letting emotion guide investing instead of reason.

Even in fixed income, investors made expensive mistakes. While the Barclay’s Aggregate Bond Index returned 6.5% over this period, the average fixed income investor had an annual return of .94%, underperforming even inflation.

Average Investor vs. Major Indices 1992 – 2011

Average stock investor and average bond investor performances were used from a DALBAR study, Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB), 03/2012. QAIB calculates investor returns as the change in assets after excluding sales, redemptions, and exchanges. This method of calculation captures realized and unrealized capital gains, dividends, interest, trading costs, sales charges, fees, expenses, and any other costs. After calculating investor returns in dollar terms (above), two percentages are calculated: Total investor return rate for the period and annualized investor return rate. Total return rate is determined by calculating the investor return dollars as a percentage of the net of the sales, redemptions, and exchanges for the period.

Threat 7: Lack of Diversification

“Don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.”

As an investor, you may have heard this old saying used to emphasize the need for a diversified portfolio.

Though diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss, a combination of asset classes may reduce your portfolio’s sensitivity to market swings because different assets — such as bonds and stocks — have tended to react differently to adverse events. For example, the stock and bond markets have historically tended not to move in the same direction; and even when they did, they usually did not move to the same degree.

Some long-term investors believe that investment success has less to do with how well you pick individual stocks or the timing of when you get in the markets and more to do with how well your portfolio has been diversified.

Just owning 10 different mutual or index funds, for example, does not mean you are effectively diversified. These mutual funds may have similar holdings or follow similar investment styles.

In addition, investors who are not properly diversified may have more risk in their portfolio or are taking risks that they are not properly compensated for.

Markets can be chaotic, but over time they have shown a strong relationship between risk and reward. This means that the com- pensation for taking on increased levels of risk is the potential to earn greater returns. According to academic research by Professors Eugene Fama and Ken French, there are three “factors” or sources of potentially higher returns with higher corresponding risks.9

1. Invest in Stocks

2. Emphasize Small Companies

3. Emphasize Value Companies

A groundbreaking study by leading institutional money manager, Dimensional Fund Advisors LP, found that exposure to these three risk factors accounts for over 96% of the variation in portfolio returns.10

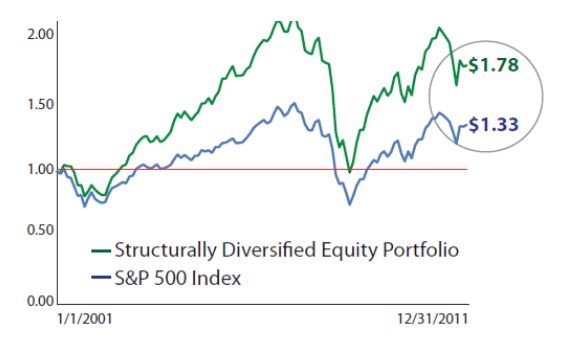

So, the presence or absence of Small and Value companies in your portfolio as well as your exposure to stocks may have a substantial impact on performance. And additional asset classes, such as Real Estate and International, help provide further portfolio diversification. To take a historical example: As the chart below shows, $1 invested in 2002 in a diversified equity portfolio including exposure to Small, Value, Real Estate, International and Emerging Markets was worth $1.78 at the end of 2011.

Growth of $1 Investment Diversified Equity Portfolio

January 1, 2002 – December 31, 2011

Diversified Equity Portfolio is weighted as 21% to the Dow Jones Total Market Index, 18% to the Russell 1000 Value Index, 15% to the Russell 2000 (Small Cap) Index, 26% to the MSCI EAFE Index (net div), 10%to the MSCI EAFE Small Cap Index, 5%to the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, and 5% to the Dow Jones U.S. Select REIT IndexData Sources: S&P 500 Index data are provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group, Russell Index data provided by The Russell Company, www.russell.com Dow Jones Wilshire Index data provided by www.dowjo- nesindexl.com; MSCI Index data provided by Morgan Stanley Capital International Group Inc. www.mscibarra.com (January 2012).

$1.78 may not seem particularly impressive…until you compare it to the S&P 500, which returned only $1.33 over the same period. This 25% difference in returns is a powerful illustration of the value of broad diversification, especially during one of the worst decades for equities in modern history.

Threat 8: No Plan

As the saying goes: “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” If you don’t know where you are going, how are you going to get there?

While retirement is a major concern for many investors, 45% of adult Americans have no plan in place whatsoever.11

But planning, especially done with professional help, can make a real difference.

Outlining your goals, identifying your risk tolerance, and setting expectations can help you stay focused on your investment strategy through bull and bear markets and strong and weak economic environments.

These are no small matters. You don’t get many chances to plan and execute your long-term financial goals.

Many prudent investors believe that the point of investing isn’t to aim for the highest possible returns, but rather to generate returns necessary to meet their long-term goals at an acceptable risk level. Attempting to enhance your returns by seeking out the needles in the haystack introduces an additional layer of active risk and the potential for increased volatility.

So what should you do? Each investor’s situation is unique, but given the challenges and expenses of active management, putting together a sound plan that entails holding a well-diversified portfolio and not trying to beat the market may be the prudent approach in attempting to achieve your long-term financial goals.

We hope you will act on the information shared in this Wealth Guide to help accomplish your goals.

1 S&P 500 Index data are provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group. Indexes are unmanaged baskets of securities in which investors cannot directly invest. Actual investment results may vary. All investments involve risk, including loss of principal. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

2 Kenneth R. French, “The Cost of Active Investing,” March 2008.

3 Barras, Laurent, Scaillet ,Wermers, and Russ, “False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas” (May 2008). Robert H. Smith School Research Paper No. RHS 06-043 Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=869748

4 Mark Hulbert, “The Prescient Are Few,” The New York Times (July 13, 2008)

5 Standard and Poor’s Investment Service, May 2009

6 Ibid.

7 New York Times, May 5, 2009

8 Performance data for January 1970-August 2009 provided by CRSP; performance data for September 2009-December 2011 provided by Bloomberg. The S&P data are provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group. CRSP data provided by the Center for Research in Security Prices, University of Chicago. US bonds and bills data © Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation Yearbook™, Ibbotson Associates, Chicago (annually updated work by Roger G. Ibbotson and Rex A. Sinquefield). Indexes are not available for direct investment. The data assumes reinvestment of income and does not account for taxes or transaction costs. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There is always the risk that an investor may lose money.

9 Cross Section of Expected Stock Returns, Eugene F. Fama and Kenneth R. French, Journal of Finance 47 (1992)

10 Dimensional Fund Advisors study (2002) of 44 institutional equity pension plans with $452 billion total assets. Factor analysis run over various time periods, averaging nine years. Total assets based on total plan dollar amounts as of year-end 2001.

11 Northwestern Mutual Market Research, April 2012

Leave a Reply